The Poetry of Aleister Crowley

{{000 Ain = Zero Absolute. 00 Ain Soph = Zero as undefinable. 0 Ain Soph Aur = Zero as basis of possible vibration}} "You and whose army?"

[Dear Mr. Aleister Crowley,]

I am writing to tell you that we have been unfortunately forced to cancel next Monday’s meeting of the [Oxford] Poetry Society. It has come to our knowledge that if your proposed paper is delivered disciplinary action will be taken involving not only myself but the rest of the members of the society. In these circumstances you will, I trust, understand why we have had to cancel the meeting.

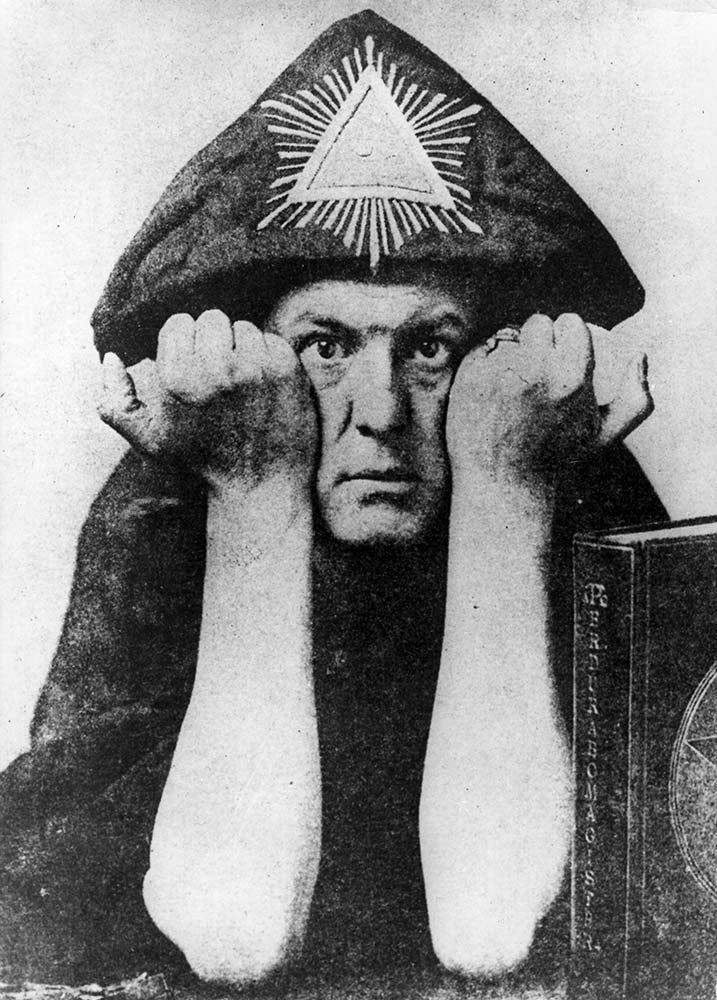

This is the statement of Mr. H. Spaight, the 1930 secretary of the Oxford Poetry Society, on the coming of the most wicked man in the world to Oxford, or that least was the brunt of his contemporary reputation.

Crowley, interviewed at his home in Kent, says the Guardian archive, ‘considered that there was “some underhand business” behind the prohibition.’ Leaving aside the accusation that he was responsible ‘for the death in Sicily of a young Oxford undergraduate, Mr Raoul Loveday’, he also said, because the subject of his talk was the medieval French magician and poet Gilles de Rais:

‘Perhaps the refusal to let me lecture has come because Gilles de Rais is said to have killed 500 children in ritual murder and in some way this was connected with myself, since the accusation that I have not only killed but eaten children is one of the many false statements that have been circulated about me in the past.’

Ladies and gentlemen, this is the notoriously underrated poet and magician whose work I present before you this afternoon, his life being stranger than fiction and yet no less horrifically immoral than false accusations of child cannibalism usually imply.

Given all this backlog, who was Crowley and what kind of poetry did he write?

Born in Leamington Spa to two parents who belonged to the Christian Plymouth Brethren, who the Thelemite Gerald Suster describes as a miserable order of cranks, Aleister Crowley was originally named Edward Alexander Crowley, although his poor mother early on determined to call him by the partly parodic, yet permanently iconic name, ‘The Great Beast 666’, or Therion, after Revelation. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography records that ‘At his father’s death, the boy became truly hostile to Christianity, for he was then transferred to the care of his uncle, Tom Bond Bishop, who was publicly philanthropic but surreptitiously cruel.'

During his stay at Trinity College, Cambridge to study Natural Sciences, Crowley suffered ‘a fevered vision [that] convinced him that all human endeavours are ephemeral, with one exception -the magical tradition. He dedicated himself to esoteric studies and sought initiation by genuine magi. Poetry greatly attracted him, and it was probably Shelley’s ‘Alastor, or, The Spirit of Solitude’ that inspired Crowley to call himself Aleister,’ on top of the fact that he considered this name, spelt the Celtic way, the most wicked in the English language.

This isn’t the only Shelley connection, In Colin Wilson’s landmark biography on Crowley, he notes that Confessions, Crowley’s 900 page autobiography, was also originally titled ‘The Spirit of Solitude.’ This is the book, by the way, in which Crowley introduces himself as poet first and magician second. Writes Wilson, “He comments typically: ‘It had been remarked a strange coincidence that one small country should have given England her two greatest poets—for one must not forget Shakespeare. And just in case the reader has never heard of Shakespeare, he adds his dates (1550-1616) in brackets, getting his birth date wrong for good measure.’

Having left Cambridge without a degree after separating from his male lover, the drag queen Jerome Pollitt, Crowley met with and was eventually initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, where, among others, he met his first magical nemesis: William Butler Yeats.

After winning over the equally egoistic and conceited leader of the Golden Dawn, Macgregor Mathers, Crowley approached Yeats, whose poetry he believed ‘lacked virility’, with extracts from his play Jephthah. One can imagine him aggressively reciting them to the bewildered poet’s face.

Oh the time of dule and teen!

Oh the dove the hawk has snared!

Would to God we had not been,

We, who see our maiden queen,

Love has slain whom hate has spared.

While Wilson notes that the profoundest poetic influence on early Crowley might have been Algernon Charles Swinburne, here at least are echoes again of Shelley, whose swirling triple rhymes in ‘The Aziola’ closely align with what you’ve heard already.

Sad Aziola! Many an eventide

Thy music I had heard

By wood and stream, meadow and mountain-side,

And fields and marshes wide,--

Such as nor voice, nor lute, nor wind, nor bird,

The soul ever stirred.

Not that it matters however, because despite Yeats admitting that ‘He forced himself to utter a few polite conventionalities’, Crowley was convinced “he could see through to the ‘black, bilious rage that shook him to the soul,’ because he instantly recognised Crowley’s incomparable superiority as a poet.’

In The Early Poetic Works by Aleister Crowley, edited and published by Christian Giudice in 2019, ‘Giudice argues that Crowley’s poetry should be seen as a part of, perhaps even the last flowering of The Decadent Movement’, seeing as Jerome Pollitt, the drag queen and lover previously mentioned, was very much involved with Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, John Gray, and Theodore Wratislaw, as well as introducing Crowley to the artist and writer Aubrey Vincent Beardsley in London.

There is a reason, however, that Crowley is not remembered for the kind of poetry he published in books like Aceldama, The Tale of Archais, Songs of the Spirit, The Poem, Jephthah, Mysteries, and Jezebel and other Tragic Poems, all of which by the way, he wrote and published between 1898 and 1899. A revealing moment in Crowley’s confessions strongly implies that under ordinary circumstances poetry did not come naturally to him, and he, in fact, only wrote it to alleviate the pressure of his repressive background.

I have always appeared to my contemporaries as a very extraordinary individual obsessed by fantastic passions. But such were not in any way natural to me. The moment the pressure was relieved every touch of the abnormal was shed off instantly. The impulse to write poetry disappeared almost completely at such periods…

It was not Crowley’s poetry that fascinated and inspired W. Somerset Maugham to caricature him as Oliver Haddo, the protagonist of his 1908 novel The Magician —it was the insanity of Crowley’s life and the possibility that even some element of his esoteric art was not fraudulent, but struck the bull’s eye at the heart of life. This brings me to the central text of Crowley’s eventually developed Thelema religion, a still extant religious belief system derived from the Ancient Greek word for: ‘Do what thou wilt.’ This is The Book of the Law, or Liber AL vel Legis. If Harold Bloom once commented that the character Hamlet possesses the only instance of authorial consciousness he has ever encountered, Crowley’s Book, if we dissimulate it from magic and treat the thing as a forty page prose poem, exudes a unique religious seriousness comparable to the tone with which the Old Testament and the Iliad speak of men and gods.

But to love me is better than all things: if under the night stars in the desert thou presently burnest mine incense before me, invoking me with a pure heart, and the Serpent flame therein, thou shalt come a little to lie in my bosom. For one kiss wilt thou then be willing to give all; but whoso gives one particle of dust shall lose all in that hour. Ye shall gather goods and store of women and spices; ye shall wear rich jewels; ye shall exceed the nations of the earth in splendour and pride; but always in the love of me, and so shall ye come to my joy. I charge you earnestly to come before me in a single robe, and covered with a rich headdress. I love you! I yearn to you! Pale or purple, veiled or voluptuous, I who am all pleasure and purple, and drunkenness of the innermost sense, desire you. Put on the wings, and arouse the coiled splendour within you: come unto me!

Here we find ourselves somewhere between the automatic writings of Yeats and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, and yet the year remains 1904!

As is par for the course with Mr. Crowley, however, this grandiose and uncharacteristically indirect writing comes from a stranger place than you could possibly imagine. Case in point: there are, according to one interpretation, three authors of this text rather than one. These are Aleister Crowley, his then wife Rose Edith Kelly, and a certain figure by the name of AIWASS. Who was Aiwass? What did he look like? Which dimension did he come from?

Just as Yeats believed his wife George was a suitable medium for the authorities, so did Crowley. He and Rose were on holiday in Cairo when she jokingly asked him to conjure ‘the sylphs’, that is the spirits of the air, only to find herself reprimanding him in their voices: “They are waiting for you.” Aiwass, if you haven’t guessed already, was the name of the demiurge or entity that Crowley managed to eke out of Rose in order to produce the Book of the Law. Supposedly, he dictated it to Crowley over his left shoulder, though whether or not he did is anyone’s guess. Yet the utter self-distancing from Crowley’s ordinary egotism is something to behold. The sin that Nietzsche mentions in his early essay Homer’s Contest, namely challenging the God of Envy, Eris, by presuming that you are equal to the gods, is narrowly avoided.

I am the Lord of the Double Wand of Power; the wand of the Force of Coph Nia--but my left hand is empty, for I have crushed an Universe; & nought remains. Paste the sheets from right to left and from top to bottom: then behold! There is a splendour in my name hidden and glorious, as the sun of midnight is ever the son. The ending of the words is the Word Abrahadabra.

The best I can do to recommend this piece of writing to critical re-examination in a non-Occult context is say that it fills in the esoteric blanks of The Waste Land, populating it with a colour and inner understanding that talk of fake Tarot cards like ‘The Drowned Phoenician Sailor’ hardly capture, let alone anticipate, seeing as it was written almost two decades before. No, as this is someone who lived and believed, however sincerely, there were astronomical consequences to the movements of his own ego -in a style uniquely separate from and nevertheless an influence on every Occult organisation developed since The Book of Law was written, I am moved to make some version of the pronouncement that Tom Holland made of Jesus Christ: that his parables are so strange and interesting, to such an extent, and with such a regularity, that it makes it genuinely probable that he was the Messiah. Who are we to doubt such weird words as Crowley’s did not come from the demiurge Aiwass?

Even if it’s a bunch of cobblers, The Book of Law makes a cracking prose poem either way.

Thank you.